Flak Read online

Michael Veitch comes from a family of journalists, and although known mainly as a performer in television and theatre, has contributed to newspapers and publications for a number of years. He has had a lifelong interest in aviation, particularly during the Second World War, and studied history at the University of Melbourne. He lives and works in Melbourne and is currently the host of Sunday Arts on ABC television.

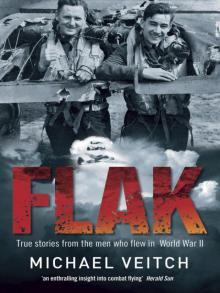

FLAK

True stories from the men who flew in World War Two

MICHAEL VEITCH

Imperial measurements have been used in some chapters of this book as they would have been during World War Two.

1 inch

25.4 millimetres

1 centimetre

0.394 inches

1 foot

30.5 centimetres

1 metre

3.28 feet

1 yard

0.914 metres

1 metre

1.09 yards

1 mile

1.61 kilometres

1 kilometre

0.621 miles

First published 2006 in Macmillan by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Limited

1 Market Street, Sydney

Copyright © Michael Veitch 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

National Library of Australia

cataloguing-in-publication data:

Veitch, Michael.

Flak : true stories from the men who flew in World War Two.

ISBN 978 1 40503 721 1 (pbk).

ISBN 1 40503721 0 (pbk).

1. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force - Airmen. 2. World War, 1939-1945 - Aerial operations, Australian. 3. World War, 1939-1945 - Personal narratives, Australian. I. Title.

940.544994

Every endeavour has been made to contact copyright holders to obtain the necessary permission for use of copyright material in this book. Any person who may have been inadvertently overlooked should contact the publisher.

Cover images from the Australian War Memorial, Negative Number UK0960 and the Argus Newspaper Collection of Photography, State Library of Victoria.

Typeset in 12.5/16 pt Sabon by Midland Typesetters, Australia Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

Papers used by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

These electronic editions published in 2008 by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd

1 Market Street, Sydney 2000

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. This publication (or any part of it) may not be reproduced or transmitted, copied, stored, distributed or otherwise made available by any person or entity (including Google, Amazon or similar organisations), in any form (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical) or by any means (photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

FLAK

MICHAEL VEITCH

Adobe eReader format 978-1-74197-158-3

Microsoft Reader format 978-1-74197-359-4

Mobipocket format 978-1-74197-560-4

Online format 978-1-74197-761-5

Epub format 978-1-74262-599-7

Macmillan Digital Australia

www.macmillandigital.com.au

Visit www.panmacmillan.com.au to read more about all our books and to buy both print and ebooks online. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events.

To the ones I never met.

Contents

Introduction

1 Gordon Dalton – Bomb-aimer

2 Dick Levy – Pilot, B-25 Mitchells

3 Allen Tyson – Air-gunner

4 Alec Hurse – Bomb-aimer

5 Les Smith – Air-gunner

6 Gerald McPherson – Air-gunner

7 Tom Hall – Pilot

8 Bruce Clifton – Pilot

9 John Trist – Bomb-aimer

10 George Gilbert – Spitfire pilot

11 Les Gordon – Air-gunner

12 Charles ‘Bud’ Tingwell – Photo reconnaissance pilot

13 Dick Thomas – Pilot

14 Derek French – Pilot

15 Pat Dwyer – Wireless/air-gunner

16 Brian Walley – Pilot

17 Ken Fox – Spitfire pilot

18 John McCredie and Lewis Hall – Pilots, brothers-in-law

19 Marcel Fakhry – Spitfire pilot

20 Trevor Trask – Pilot

21 Norman Robertson – Catalina pilot

22 Ron English – Navigator, Dakotas

23 Tom Trimble – Fighter pilot

24 Arch Dunne – Bomber pilot

25 Walter Eacott – Beaufighter pilot

Postscript

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Michael Veitch has done a fine job of getting those of us who were shot at a lot in the skies of World War II to talk about things we seldom discussed in great detail – anywhere. Though I had many friends in heavy bombers I was never in one myself. My Mosquito navigator had been shot down on his first tour in a Beaufighter – then came to me. I had friends on long range Coastal Command aircraft, on medium bombers, on fighter squadrons and low-level ground attack. Not many survived.

The accurate descriptions in this book taught me so much, almost for the first time. I may have been frightened on several occasions in my job as a photographic reconnaissance pilot but I have often wondered if I could have done what other air crews had to do. That any of us survived at all, regardless of what our duties were, is sometimes hard to believe. Thank you, Michael, for illuminating so much about so many.

Charles ‘Bud’ Tingwell, 2006

Introduction

An Obsession

Inside the head of every pilot, navigator or gunner

who flew during the Second World War is at least one

extraordinary story.

One of the best I heard was from a bloke I never got to meet. He was a rear-gunner in a Lancaster bomber and as such, sat away from his six fellow crew members at the back of the plane, shut inside a tiny perspex and aluminium cage right under the tail. A hydraulic motor powered by a relay in one of the bomber’s four engines allowed him to swivel back and forth through slightly more than 90 degrees while the four mounted machine guns tracked vertically, protruding rearwards through the turret, controlled by a small hand grip. The trick was to coordinate the sideways movement of the turret with the vertical movement of the guns and bead in on a moving target, usually an enemy night fighter, in an instant. In 1943 this was brilliant technology. Indeed, the aircraft itself symbolised the absolute upper limit of what was achievable both technologically and industrially at the time, and required a massive – some have argued disproportionate – investment of Britain’s wartime resources.

Inside the turret there was virtually no room, not even for the gunner’s parachute, which had to be stowed on a shelf inside the fuselage and separated from the turret itself. So, if the moment came to jump, he would need to open the two small rear doors, climb back into the fuselage, locate the ’chute, strap it on, then make his way forward and leave the aircraft via the main door, presumably while being thrown about as the mortally wounded aeroplane went into its death spin from 20,000 feet. Easier said than done.

As the story goes, this fellow was directly over the target on a big night raid into Germany, his aircraft right above one of the large doomed cities being systematically wrecked by fleets of up to a

thousand RAF heavy bombers at night, and possibly the Americans by day. Peering into the black sky, he swept his guns up and down, back and forth, watching for enemy fighters. Some of them reckoned that by just looking busy you appeared more alert to the German pilots and were less likely to be attacked. Suddenly he saw something – a dark shape moving fast – possibly another bomber, possibly a German night fighter passing underneath. As he leaned forward over his guns to gain a better view he felt two mighty almost instantaneous bangs and something slither quickly down his back. The turret instantly stopped working, making the guns inoperable, but both he and the aircraft seemed otherwise undamaged. He looked up. Inches above his head he saw a baseball sized hole in the top of the turret and underneath it, a matching one in the floor. It took only a moment for him to work out what had happened. An incendiary bomb – a small aluminium pipe crammed with magnesium and dropped in their hundreds – had fallen from another bomber above and passed clean through the turret before continuing on its way.

At night, with inexperienced pilots and up to a thousand four-engined aircraft passing over the same target in roughly 20 minutes, being bombed by your own side, not to mention mid-air collisions, were just a couple of the occupational hazards of flying with Bomber Command during the Second World War. Were it not for the fact that this fellow just happened, in that very instant, to be looking out for something he wasn’t even sure was there, he would have certainly been killed. As it was, his turret was useless and he could only hope a night fighter didn’t decide to pick on him on the way home. This night he was lucky.

As this was being told to me in the living room of a modest unit in a suburb in Perth, my jaw was agape and a cup of undrunk tea sat cooling in my hand. In the coming months, as I collected similar stories from the men, now in their eighties, who flew the aircraft of the Second World War, I would assume a similar position many times.

‘So what got you interested in this stuff?’, people ask me when the subject comes up unexpectedly, wearing a look on their face as if they’ve just digested something unsavoury. Dwelling on the awfulness of war is hardly the healthiest of mental occupations I admit, so I don’t talk about it much. I usually just mumble, a little embarrassed and skirt the topic. Because in reality, I have no idea, and I’ve often asked myself the same question: how did I get interested in this stuff? I’m not particularly aggressive, am a complete coward when it comes to any form of confrontation and being involved in a war is just about the most appalling thing I can imagine. But I can’t deny that the fascination is there, lodged deep inside me, and I’m not expecting it to go away anytime soon. I conveniently put it down to the unavoidable effects of growing up virtually as an only child in a semi-dysfunctional family. I was the youngest of four by about ten years, and an accident. Apparently, I owe my existence to a noisy and persistent mosquito buzzing around my parents’ bedroom late one summer night, ‘The night of the mosquito!’, as my mother would spontaneously announce to anyone who would listen, amusing herself enormously at my expense.

My siblings wisely left home as soon as they could in their teens, so I was left to ferment in the eccentricities that most only children tend to develop. Mine happened to be aeroplanes. Model aeroplanes. I made hundreds of them and by the time I was ten could identify everything that flew between about 1937 and 1945. I spent every cent I had in hobby shops and made up the plastic kits of Spitfires, Typhoons, Blenheims and Lancasters. But it was never enough just to have them on a shelf. In my bedroom I constructed a complicated overhead mesh of string and fuse wire and arranged them in simulated combat, even building several of the same types to make up the numbers for realism. I developed a rudimentary light show using torches and standard lamps to simulate an air raid, and those planes for which I had no further use would end their days in fiery backyard dioramas of firecrackers and melted plastic. My fingers became permanently dried and wrinkled from the glue and my mother, fed up with the permeating odour of turpentine and enamel paint, exiled me to a corner of an upstairs balcony where, it now seems looking back, I spent the larger part of my childhood, summer and winter.

Many boys of that age go through a similar stage, but then grow out of it. I just never did. Failing that, one could reasonably have expected me to evolve into the jet age but that never really took off either. Although one year I did try to force myself, and put together the Airfix Hawker Hunter, perhaps the most elegant jet aircraft ever built, and even the mighty Vietnam-era Phantom (more like an airborne truck). But I could never come to terms with jet propulsion and soon regressed once again to propellers.

I have no military tradition to fall back on. My father thought about enlisting in World War Two but was too young; I did have an uncle in the army but bad feet prevented him from ever leaving the country, and a grandfather (I barely knew him) who spent some time on minesweepers in the navy. I still keep his medals in the same old Sheaffer pen case in which they were given to me, and that, I’m afraid, is where the Veitch military heritage begins and ends.

Well, not quite. In order to avoid the call-up for Vietnam, older brother Simon spent some time at Puckapunyal, north of Melbourne, in something called the Citizens Military Force, and I remember being enormously impressed by his uniform during weekend family visits.

Then in the mid 1970s, the landmark British documentary series The World at War screened on television at a time coinciding with a particularly hideous period in my parents’ often strained relationship. In front of a small grey plastic AWA television set, I sat mesmerised by the black and white images of a distant and terrible conflict, which had the effect of blotting out that other war raging around me in my own world, the relentless set-piece battles played out on the field of my father’s affairs and my mother’s depression and drinking. For hours I would shut my eyes, try to ignore the shoutings in the night, and concentrate hard on what it must have been like to have actually been there, not in black and white but in real, living colour. It was my perfect mental escape hatch. One particularly gruesome evening I lay in bed for hours pondering the bakelite light switch on the wall I used every day. In a moment of revelation, it occurred to me that someone must have made and installed the thing before the great conflagration had even started.

I watched every episode of that series, my head spinning with the sounds and images for days afterwards. One part on the Russian war featured the recollections of four or five men and women, all veterans of the slaughter on the Eastern Front, recounting the tragedy in stupefying detail. At the end of the episode, the camera re-visited each one of them in turn in a kind of recapitulation, as they simply gazed into some middle distance behind the camera, pondering the scale of what they had seen and done in agonising, eloquent silence.

But it was the air force stuff that really fired off the the synapses of my early adolescent imagination. Then, on a Sunday afternoon in 1976, aged thirteen, I made an expedition to a small museum, which was, and still is, attached to Melbourne’s light aircraft airport, Moorabbin. I fervently refused my father’s offer to drive me (he loved an excuse to get out of the house) and eagerly plotted the complicated Sunday afternoon timetable myself. This was one childhood expedition I wanted to savour entirely alone.

After a train ride and some interminable waiting at suburban bus stops, I eventually got there. Entering the museum was like walking into a kind of paradise. Bits of old aeroplanes were scattered all over a vast yard that I was permitted – welcomed even – to crawl all over. The nose section of a Beaufort here, the wing of a Fairey Battle there. And then there were the complete types, including one of the meanest aircraft of the war, the magnificent Bristol Beaufighter – twin engined with a tall single tail fin, four evil-looking slits under the nose to house its 20-millimetre cannons and two enormous Bristol Hercules radial motors extending slightly beyond the nose, further exaggerating its immense power. Used by Australia in the Pacific, its dark grey livery gave it the appearance of an immense marauding shark.

I walked around it awe-

struck. It seemed almost alive. But there was more. Up the back stood a single seat fighter, a P-40 Kittyhawk, used by the RAAF in the Middle East and in the early stages of the Pacific war. About the best thing that can be said about this machine was that it could take a lot of punishment, which was just as well, because it was frequently required to do so. Although well armed, it was big, slow and heavy – inferior to just about everything it went up against. Built by the Americans in the late 1930s, it was outdated even on the drawing board but times were desperate and it was rushed into production. The only way it could make an impact on the nimble Japanese planes was fall on them from a great height, blast away hopefully and just keep on going downwards, ably assisted by gravity. Those Kittyhawk pilots foolish enough to take on a Zero were often living their last moments. But despite its shortcomings, I was in a forgiving mood and delighted to make its acquaintance nonetheless.

This particular Kittyhawk had not only survived the war but had been given a new lease of life by enthusiastic volunteers who had restored its Allison engine (an appropriately underwhelming name) to a point where it was very occasionally started up. As luck would have it, this Sunday afternoon was one of those occasions. I stood back and watched as a couple of devotees attached a large and ancient trolley accumulator (an antiquated portable battery) to a socket in the fuselage. The enormous propeller then jolted and then roared into life for ten glorious minutes. Suddenly this dilapidated museum piece, outmoded even in its day and half decayed in a scrapyard was, before my eyes, resurrected into the very essence of power. It was like seeing a dinosaur come back to life and start roaring.

The other aspect of that day, I remember, was a total solar eclipse that eerily blotted out the daylight during the bus trip on the way home. But for me, it was by far the minor event of the day!

Turning Point

Turning Point Heroes of the Skies

Heroes of the Skies The Forgotten Islands

The Forgotten Islands Hell Ship

Hell Ship Flak

Flak Fly

Fly